When Justice Fades, Recklessness runs free” In memory of my late brother”

Introduction

Born into the vibrant but often challenging terrain of Guyana, Dr. Will Alexander Pluck was shaped not by ease but by expectation. Raised by a single mother in a modest home, his early life was defined by strict moral discipline, faith-based routines, and a deep awareness that life was never about him—it was about others.

Even before he could write essays or mix pigments, Dr. Pluck understood responsibility. His mother, firm but nurturing, made it clear that mediocrity was not an option. She demanded order, prayer, cleanliness, academic excellence—and perhaps most importantly, accountability. While the absence of a father left silence in some corners of his childhood, it was filled by her unwavering presence, a maternal compass that pointed him always toward truth.

His early schooling revealed a student not only talented but thoughtful. Though he faced challenges, especially when transferred to a less recognized secondary school, he never used limitations as excuses. Instead, they became catalysts. He read more. He practiced longer. He observed deeper. Art, even then, became his outlet—not just to escape reality, but to reshape it.

Dr. Pluck’s first official teaching assignment was at the prestigious St. Rose’s High School in Georgetown. Within just his first year, his students achieved remarkable success—winning both Gold and Supreme Gold medals in international art competitions. His efforts earned him the Best Teacher of the Year award (1983–1984).

At the E.R. Burrowes School of Art, young Will found a space that recognized his rare mix of vision and discipline. He excelled in painting, drawing, history, sculpture, and printmaking, completing his diploma with distinction. His leadership was evident—twice elected as President of the Student Union—and his talents undeniable. He wasn’t simply a good student. He was, as Director Denis Williams wrote, “among the few truly original and gifted artists” to emerge from the institution.

Phase 1 : Roots of Resolve

Childhood, Motherhood, and the Making of a Man

The early life of Dr. Will Alexander Pluck was not marked by extravagance or applause, but by the kind of quiet, consistent discipline that turns boys into pillars. He was born in Guyana, a nation of vibrant culture and resilient people, and raised under the unwavering authority of a woman who would become the single most powerful influence in his life—his mother.

She was both mother and father, provider and protector. Her house was governed not by fear, but by expectation. Prayer before school, punctuality without excuse, chores done with pride, and words spoken with respect—these were not negotiable customs; they were the fabric of the household. From her, young Will learned early on that life owed him nothing—but faith, focus, and fortitude would open doors no one could shut.

Dr. Pluck would later speak of her not with sentimentality, but with reverence. “She gave me the fear of God and the fear of wasting time,” he often says. And in those twin truths, his life began to take shape.

The absence of his father was never denied—but it was never used as an excuse. Instead, his uncle stepped in as a quiet guide, especially during his teenage years, providing structure, advice, and masculine energy rooted in faith and dignity. Yet, it was his mother’s spirit that towered above all. She ensured that every one of her children—especially her sons—knew what was expected of them. She demanded strength, because she had no other option but to be strong.

As a child, Will showed early signs of observation and reflection. He wasn’t loud, but he was present. He didn’t seek the center, but he always understood the whole. These qualities—discipline, presence, humility—would later form the core of his artistic and educational philosophy. But at the time, they simply made him a boy with depth.

His earliest memories were steeped in Christian tradition and community ethics. Sunday school, gospel music, the sound of prayer humming through the walls at dawn—these moments weren’t decoration; they were definition. They taught him that success was not measured by possessions but by how much you gave, how well you listened, and how deeply you believed.

Schooling in Guyana was rigorous, especially for those with limited resources. At one point, Will attended a school perceived as “modest” but good reputation. For many, it would have been a setback. For him, it was a challenge. He dug deeper, studied harder, and worked silently. He was determined that his excellence would not be decided by someone else’s labels.

Phase 2 : Canvas and Conscience — Artistic Training and the Birth of a Cultural Voice

“Art is not a mirror held up to vanity. It is a lens sharpened by truth.”

As the door to formal education opened at the E.R. Burrowes School of Art, Dr. Will Alexander Pluck stepped into a space that would shape not just his technique—but his philosophy. He didn’t come to Burrowes merely to learn how to paint or sculpt. He came to uncover what it meant to be an artist with purpose, a teacher of vision, and a voice for the voiceless.

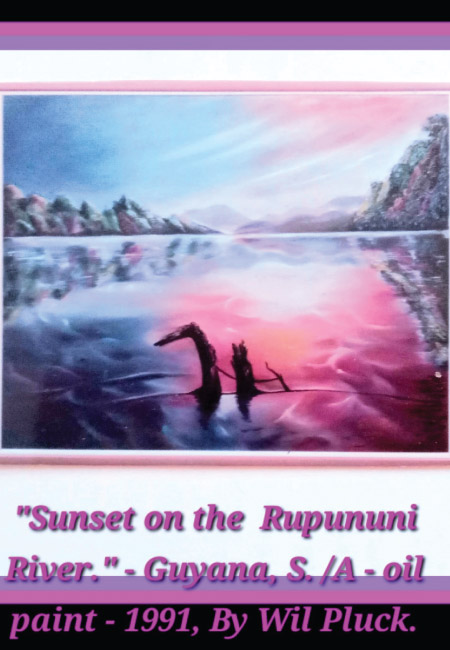

From 1978 to 1982, Dr. Pluck immersed himself in five core disciplines—Painting, Drawing, History, Sculpture, and Printmaking. Each subject did more than stretch his skill—it revealed to him the deeper potential of his gift. For him, art was never an end in itself. It was a language, a weapon, a witness. Something to speak when others were silenced. Something to preserve stories, critique injustice, and elevate the unseen.

At Burrowes, Dr. Pluck’s excellence quickly set him apart. His instructors recognized not only his precision and creativity, but also his quiet leadership and piercing moral clarity. He was twice elected President of the Students’ Union, a rare achievement that reflected how deeply his peers respected him—not for popularity, but for principle. He led not with ego, but with ethics. Not with authority, but with empathy.

Among those who would formally recognize his promise was Denis Williams, then Director of Art & Archaeology. In a professional recommendation, Williams wrote that Will Pluck stood among “the few truly original and gifted artists” to have passed through the school. That statement, coming from a man of such stature, was not a compliment—it was a coronation.

But Dr. Pluck was never swayed by praise. He remained rooted in the conviction that art without integrity is decoration. And decoration, while beautiful, cannot liberate the oppressed, cannot reform broken systems, cannot teach a child to believe in themselves. For him, art had to do more.

This belief began to materialize in his earliest works—raw, emotive, unapologetically honest pieces that challenged the traditional Caribbean aesthetic of “sun, sand, and sea.” Where others painted the postcard, he painted the protest. Where others showed the landscape, he revealed the layered psychology of a people struggling for identity, power, and purpose.

Phase 3 : Voices in Color — Art, Teaching, and the Pursuit of National Dialogue

“When art educates and education heals, the soul of a nation begins to rise.”

For Dr. Will Alexander Pluck, the end of formal training at the E.R. Burrowes School of Art marked not a conclusion, but a beginning—a mission now in motion. Having mastered the disciplines of visual storytelling and historical critique, he transitioned into a phase that would amplify his voice, extend his reach, and begin to define him not just as an artist, but as a moral educator and public intellectual.

It was during this time that Dr. Pluck made one of the most defining choices of his life—to teach. Not simply to instruct techniques, but to form minds. Not just to pass on information, but to spark conscience. Teaching, for him, was never a job. It was a spiritual calling—a way to shape not only the hands of young artists but the hearts of future leaders.

From his earliest days in the classroom—beginning in Guyana and later in the Bahamas—it became clear that Dr. Pluck was no ordinary educator. He refused the traditional models of detached instruction. He brought energy, storytelling, challenge, and truth to every lecture.

He would arrive early, stay late, and speak with gentleness even while delivering hard truths. His message was always clear: “If you cannot paint with purpose, put the brush down.” For Dr. Pluck, the classroom was not a sanctuary from the world—it was a rehearsal for service in it.

He taught them how to see—not just visually, but morally. “Notice what’s missing in the painting. Then ask yourself what’s missing in your society.” His lessons often ended not in applause but in silence—the kind of silence that comes when a student realizes they’ve just been given something sacred.

During these years, Dr. Pluck created some of his most iconic pieces—works that served not only as aesthetic marvels but as tools of social commentary and cultural resistance.

Take, for example, “To His Greater Glory.” Painted around 1993, this piece is a visual storm of devotion, conflict, and divine chaos. Angular bodies, dramatic movement, and ethereal light collide in a battlefield of faith. It is not simply a religious painting—it is a reflection of internal war. The war between ego and obedience, society and salvation, flesh and spirit. It challenged not only secular viewers but believers to reconsider what true worship looks like when justice and truth are at stake.