The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service of others.

Dedication

“In family life, love is the oil that eases friction, the cement that binds closer together, and the music that brings harmony.”– Friedrich Nietzsche

This book is lovingly dedicated to my family—the silent strength behind every step I’ve taken and every seed I’ve sown.

To my beloved wife, Veronica Nachuch, your unwavering love, patience, and encouragement have been the roots that kept me grounded even in the strongest winds. Thank you for believing in the mission and standing by my side through every challenge, every journey, and every sleepless night.

To my children, Pamela, Irene, Faith, and Linda, your laughter, curiosity, and questions about the world inspire me to make it better every day. May this book serve as a testament to the importance of caring for our planet—and may you grow up with the courage to protect it even more fiercely than I have.

To my late parents, Natukoi Ewoi and Fidelis Timotheo, my late elder sister Elisabeth Lotiyan (may their souls rest in eternal peace), and my extended family, thank you for the values of hard work, humility, and service you instilled in me. Your blessings continue to guide my path, wherever I go.

This story is not mine alone—it is ours. And it is my greatest joy to dedicate it to you.

With all my love,

– Dr. Peter Mawaitho

PHASE 1: Roots Beneath the Soil

“He who plants a tree plants hope.”– Lucy Larcom

Long before the world called him “Doctor,” long before international agencies recognized his contributions, and before academic titles followed his name, Peter Mawaitho was simply a young man standing in the arid yet resilient soil of Samburu County, Kenya—looking at the land not as it was, but as it could be.

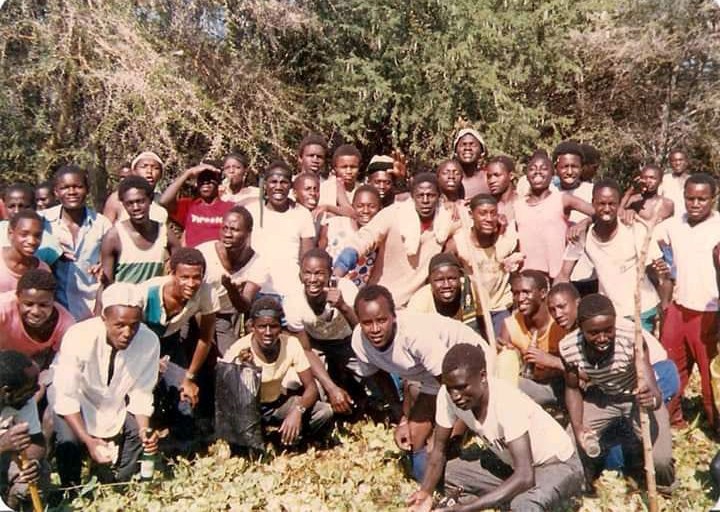

It was the mid-1990s. Droughts were more frequent, livestock thinner, and the forests that once provided shade, food, and fuel were retreating with alarming speed. Freshly armed with academic training in range management and a heart full of purpose, Dr. Peter joined Farm Africa Kenya as a project officer. For many, it was just a job. But for him, it was a calling—the first seed in a lifetime of service to the Earth.

He arrived not with lofty speeches, but with listening ears. He walked through villages, sat under thorny acacia trees with elders, joined youth groups on nature walks, and shared tea with women carrying bundles of firewood on their backs. He understood something profoundly important: conservation cannot be imposed—it must be cultivated from within the culture, values, and needs of a community.

Dr. Peter quickly earned the trust of local people by grounding his initiatives in relevance. His first major intervention was deceptively simple: fruit tree nurseries. To many, trees meant shade or firewood. But Dr. Peter introduced a vision where trees were also livelihoods. Mangoes, papayas, citrus—he brought in saplings and paired them with practical training on grafting, watering techniques, and soil conservation. The trees grew, and so did hope. Children began walking past orchards on their way to school. Mothers sold fruit at market stalls. The barren land began to turn green, one sapling at a time.

But he didn’t stop there. He knew that true sustainability required more than planting; it required income alternatives that worked with nature, not against it. That’s when he turned to the ancient art of beekeeping—modernized for new purpose.

Under his leadership, communities were introduced to modern beehives, strategically placed along forest edges and within fruit orchards. The bees did more than make honey; they pollinated the very trees he had planted. It was nature working in harmony, with Dr. Peter as its quiet conductor. The sale of honey became a new stream of income for many families, especially women and youth, who took pride in managing the hives. Beekeeping clubs were formed. Trainings were held under trees. The buzz of bees became a symphony of regeneration.

As his work expanded, so did his responsibilities. Dr. Peter began monitoring and evaluating environmental projects across the region, developing indicators to measure not only the growth of trees but also the growth of people—in awareness, resilience, and economic stability. He paid attention to detail: rainfall patterns, soil degradation rates, seedling survival percentages. But more importantly, he paid attention to people’s stories, struggles, and aspirations.

His approach was always holistic. He would often say, “You can’t protect trees if people are hungry.” This philosophy became the backbone of his work. His model of conservation was community-centered, anchored in local knowledge, and sustained by local ownership. That’s what made it last. Long after his official tenure at Farm Africa Kenya ended in 1999, the orchards he helped start continued to bear fruit—both literally and figuratively.

But Samburu was more than his first assignment—it was his crucible. It taught Dr. Peter lessons no classroom could. It showed him that ecology without empathy is empty, that policy without participation is powerless, and that hope often grows slowly, like a sapling—but when nurtured, it can transform landscapes.

His ability to endure challenges had deep roots. At 13, when he went to boarding school for the first time, he was away from his parents for a full year. It was a hard but formative experience—teaching him independence, responsibility, and accountability for his actions. At 21, he married, and soon after, began raising a family. These early responsibilities shaped the resilience, focus, and commitment that would define his life’s work.

PHASE 2: The Forest Whisperer

“The environment is where we all meet; where we all have a mutual interest; it is the one thing all of us share.”– Lady Bird Johnson

The forest doesn’t speak in words—but Dr. Peter Mawaitho learned to understand its language. He could hear it in the rustling of dry leaves, in the silence of cut stumps, and in the sigh of winds sweeping across barren hills where trees once stood tall. By the time the new millennium dawned, Dr. Peter had begun to emerge as something rare: not just an environmentalist, but a forest whisperer—a quiet yet powerful voice that spoke both for the people whose lives depended on it.

Real success began in 1994 when he got his first job with a non-governmental organisation (Farm Africa-Kenya) as a project officer in charge of the environmental department. During this time, he gained more practical experiences in environmental issues, resource conflict resolution, and transforming nomadic societies in Kenya.

His growing expertise and rising reputation led him from the familiar soils of Kenya into new terrain. In 1999,

He joined Resource Projects Kenya, where he expanded his advocacy for environmental conservation by working directly with rural communities to raise awareness on forest protection and sustainable land use. It was a role that bridged knowledge with grassroots action—one where Peter spent long hours in community halls, village councils, and beneath trees, educating farmers, elders, and schoolchildren alike on why the forest was more than a source of firewood—it was a lifeline.

But it was his next chapter that would truly test his conviction and expand his influence.

In the year 2000, Dr. Peter embarked on a transformative journey beyond the Kenyan border. He was selected to serve with Volunteer Services Overseas (VSO) in Nigeria—an opportunity that would mark a pivotal evolution in his professional and personal philosophy. As an Environmental Protection Specialist stationed in Sokoto and other parts of northern Nigeria, Dr. Peter was no longer just teaching about trees—he was rebuilding relationships between people and nature, between policy and action, and between environment and justice.

The challenges in Nigeria were vast. The region suffered from deforestation, desertification, poverty, and fragile social structures. Fuelwood was the primary energy source, and trees were vanishing rapidly to meet daily cooking needs. To many, environmental protection seemed like a distant concern—something for academics or international agencies. But Peter knew otherwise. He had seen firsthand how a degraded environment could deepen poverty, hunger, and displacement. And he knew that the key to transformation was not enforcement—it was empowerment.

He began by mobilizing local communities—not with top-down orders, but through trust, empathy, and shared vision. Working with a consortium of community environmental conservation groups, Dr. Peter launched a bold afforestation campaign. He established tree nurseries, introduced fast-growing drought-resistant species, and trained local volunteers in how to nurture saplings into maturity. Tree planting became a communal ritual—villagers, students, and elders alike took part in what Dr. Peter called “reclaiming the future.”

But his brilliance lay in understanding that the environment could not be separated from human rights and social justice.

While greening the land, Dr. Peter was also feeding children. Through VSO’s outreach programs, he helped raise funds to support child rights activities, including feeding programs in street children rehabilitation centers. He worked tirelessly to create awareness about the rights of children to food, safety, and education. He saw these issues not as separate silos—but as interconnected roots of the same tree. To him, environmental justice and human dignity were two branches of the same mission.

PHASE 3 The Culinary Story

“In the long term, solar power is the only way to go.”– Gregory Benford

By 2003, the whispering trees of Nigeria had heard Peter Mawaitho’s voice. Now, the sun would begin to respond.

That year, Dr. Peter Mawaitho took on an ambitious short-term consultancy role with Shell Oil Company in Nigeria—but not in the way one might expect from a major oil conglomerate. Rather than drilling into the Earth, Peter was looking up—to the sun, and to the untapped promise it held for millions of African families living without access to clean, affordable energy.

In the rural villages and peri-urban communities across Nigeria, the daily act of cooking was a ritual burdened with danger, drudgery, and environmental harm. Women—often with young children strapped to their backs—walked for miles in search of firewood. Trees fell daily to meet the demands of fuel. The smoke from open fires blackened the walls of huts and the lungs of children. Burns, respiratory illnesses, and deforestation were the price of a hot meal.

Working closely with engineers, local artisans, and community members, Dr. Peter led the development of affordable, efficient, and replicable solar cookers that could withstand the harsh West African climate while being simple enough for widespread adoption. The design was elegant in its practicality: a parabolic reflector to capture solar rays, a heat-resistant box to trap energy, and basic insulation to retain cooking temperatures. The materials? Sheet metal, mirrors, glass panels, cardboard, and clay—all readily available or easily adapted.

But the true brilliance of the project lay not in the hardware—it lay in how Dr. Peter brought people into the process.

He didn’t just hand out solar cookers. He trained women’s cooperatives, youth groups, and village elders on how to use them, repair them, and most importantly, understand their environmental value. Demonstrations were held in village centers. Pilot families were selected to test the cookers and provide feedback. Recipes were adapted to solar timing. Children came home from school to see their mothers cooking without smoke. And slowly, something extraordinary began to happen.

The use of firewood declined—by a staggering 80% among participating small-sized households. The surrounding trees were no longer sacrificed daily for fuel. Women had more time in their day and fewer health complaints. Youth groups began building their own models and replicating them in nearby villages. Some even sold them, creating small business opportunities that tied sustainability with income generation.

Dr. Peter’s solar dream was taking root—quietly but powerfully. What began as an alternative technology experiment grew into a community-driven renewable energy initiative that rippled across the region. The project not only aligned with environmental goals, but with gender empowerment, youth development, and poverty reduction.

The impacts were multi-layered:

Environmental: Deforestation slowed in areas where solar cookers were widely used. Local forests that had once been stripped of wood began to recover. Carbon emissions from open fires dropped dramatically.

Health: Women and children suffered fewer respiratory illnesses, burns, and smoke-related infections.

Economic: Households spent less on purchasing wood or charcoal. Time saved from firewood collection was redirected into small-scale farming, schooling, and family life.

Social: Communities felt empowered by a solution that came from within, not imposed from the outside.

Dr. Peter became widely recognized—not just within Shell, but in the broader development and environmental communities—as a grassroots innovator in renewable energy. Unlike many who talked about clean energy in abstract terms, he delivered practical tools that worked, were owned by the people, and could scale.