Foreword

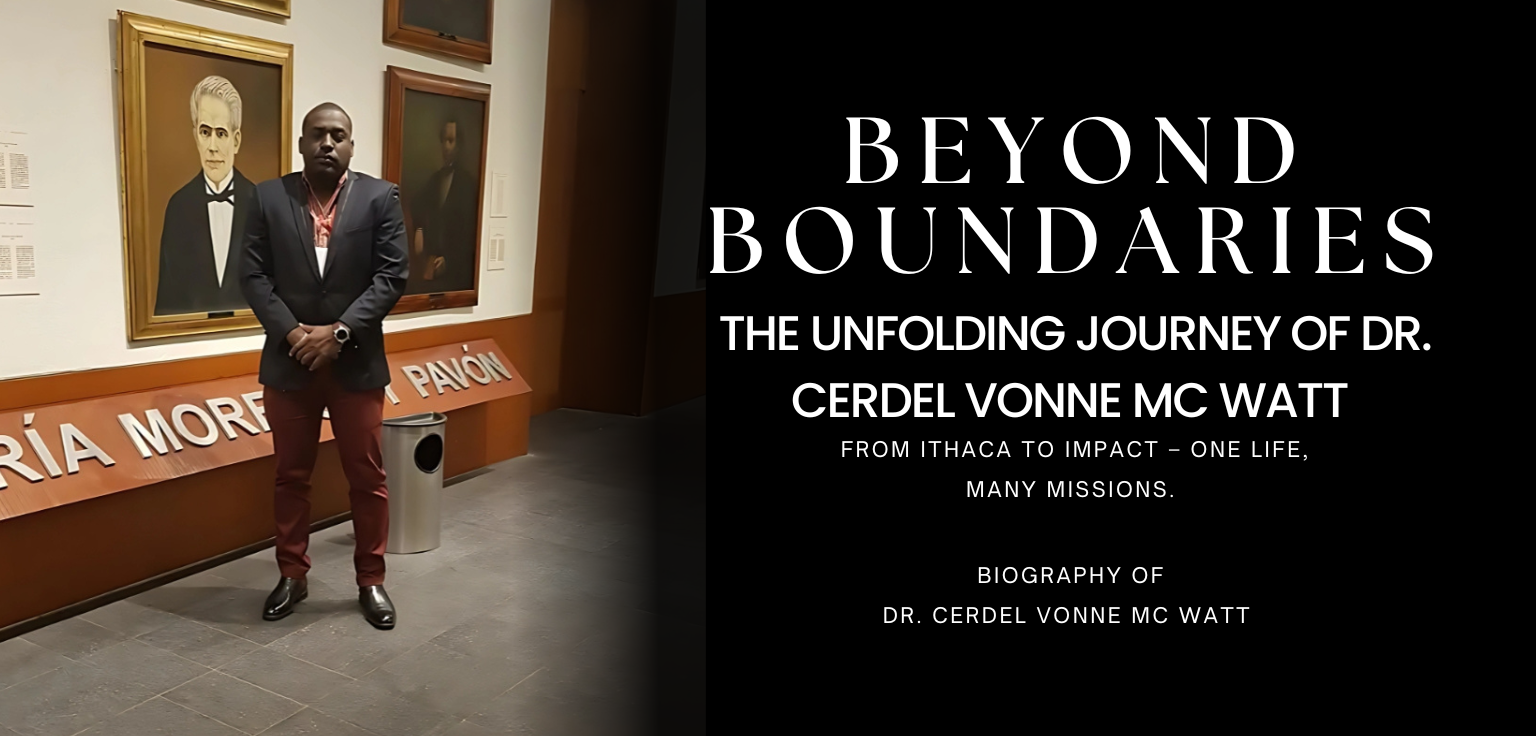

It is my distinct pleasure to introduce “Beyond Boundaries: The Unfolding Journey of Dr. Cerdel Vonne Mc Watt.” Over the past decade, I have observed Dr. Mc Watt’s trajectory with admiration—from his early work as a veterinary public health inspector to his current role shaping policy and practice across Guyana’s ten administrative regions. His unique blend of clinical expertise, administrative acumen, and cultural sensitivity has strengthened public health infrastructures in communities that were once underserved and overlooked.

Dr. Mc Watt’s capacity to navigate diverse spheres—agriculture, teaching, medicine, and health systems management—speaks to a rare versatility. His stewardship during the COVID-19 pandemic, leading both cold-chain logistics and community mobilization efforts, stands as a testament to his strategic foresight and collaborative spirit. Vaccination rates shot up, and public confidence was maintained under his management, even during times of worldwide turbulence.

His differentiation factors are not only the breadth of his achievements, but also the depth of his beliefs; he is still Dr. Mc Watt. He comes to every problem with a servant-leader’s mentality and understands that while health equity requires resources, it also requires relationships. His mentoring of young leaders and the active elevation of unheard voices has made a real difference for change.

When you turn the next set of pages, be ready to meet a life that is hard to sum up concisely in a single word: a clinician… educator… strategist… and, at their core, a poet. But, even more, you will meet a living embodiment of hope and service whose echo is felt far beyond the shores of Guyana.

— Professor Amara Lewis, PhD

Dean of Public Health, Caribbean University

PHASE 1: Seeds of Ambition Early Education & First Aspirations

“In the silence of small-town air, A dream was born, bold and rare, To heal, to serve, to mend, to be, A soul of light for all to see.”

The hamlet of Ithaca, perched on the banks of the Corentyne River in Guyana’s East Berbice–Corentyne region, is far removed from the cosmopolitan circles of global health where Dr. Cerdel Vonne Mc Watt now moves with ease. Yet, it was among Ithaca’s 450 or so inhabitants—predominantly of African descent—that the seeds of his ambition first took root. Born the youngest surviving child in a family of three, Cerdel learned early that life’s fragility and promise often walk hand in hand.

His childhood home—a modest wooden dwelling shaded by mango and coconut trees—was filled with laughter, hymn singing, and the gentle creak of a hammock under the Caribbean sun. His father, Colin Fitzpatrick Mc Watt, left for French Guiana when Cerdel was scarcely one, joining the fishing vessels that plied the Atlantic. From afar, Colin sent what he could, sustaining the family’s modest security. His mother, Sandrina Yvonne Mc Watt, balanced her duties as an overseer for the Neighbourhood Democratic Council with the tireless devotion of raising three children. Compassion and steely resolve were constant in their home—traits that would later define Cerdel’s own journey as a servant-leader.

One of the most defining events of his childhood was the tragic loss of his younger sister, his mother’s fifth pregnancy. She was four years younger than Cerdel, yet her life ended before it could truly begin. He vividly recalls noticing the absence of movement in her tiny body—strange, silent, and deeply unsettling. For three days, the young boy sat beside her cot, willing life into her through sheer imagination. Only after convincing himself that something was truly wrong did he report it to his mother. Even at that tender age, Cerdel displayed an uncanny attentiveness to the subtlest signs of life and an instinct to speak in gentle, comforting language. This moment, though heartbreaking, became a lifelong motivator—a quiet vow to understand and fight for life whenever he could.

At Ithaca Primary School, learning was personal and simple. There were no digital classrooms, robots, or modern laboratories—only chalkboards, worn textbooks, and readers that could be recited under the shade of mango trees. Cerdel excelled, not for recognition, but out of a deep, genuine curiosity. After lessons, he often lingered over borrowed biology primers, tracing diagrams of the circulatory system in the dusty courtyard.

His enthusiasm was no secret. Neighbours would smile as they saw the boy running home, schoolbag bouncing, eager to share the day’s discoveries. “Mama, today I learned how blood cells carry oxygen!” he would exclaim. To him, the human body was not just a structure but a living puzzle—one whose threads could be untangled and repaired with the right knowledge and tools.

Secondary school awaited across the river in New Amsterdam. Each morning, before sunrise, he boarded the ferry with a small group of students, braving the turbulent waters to reach the Berbice Educational Institute in an Indo-Guyanese community. Here, classrooms overflowed with pupils, and the lively chatter of Ithaca was replaced by intense academic rivalry. Cerdel adapted quickly, making friends across cultures—playing cricket one week with the sons of sugarcane workers, studying Shakespeare the next with the daughter of an estate overseer. It was here he began to see that health was not shaped by biology alone, but also by culture, tradition, and community.

Financial limitations stood as the greatest barrier to pursuing his dream of medical school. Family priorities shifted, and overseas tertiary education in medicine became impossible at that stage. Determined to find a path that still allowed him to serve, he followed peers into agriculture, enrolling in a diploma program at the Guyana School of Agriculture just outside Georgetown. It was a detour he could never have predicted, yet he approached it with the same dedication he had once reserved for the study of the human body.

Still, each evening, under the stars, swaying gently in his hammock, he would whisper to himself: “Someday, I will wear that white coat.” The diagnosis he once made for his sister—innocent yet deeply human—remained etched in his mind as a reminder of the stakes of medicine. Whatever direction his path might take, he vowed, it would one day circle back to healing.

PHASE 2: Detours of Destiny Agriculture, Teaching & First Jobs

“Success is not final, failure is not fatal: It is the courage to continue that counts.” — Winston Churchill

Once Dr. Cerdel Mc Watt graduated from the Guidance School of Agriculture, it seemed inevitable that he would step into the sugar estates and rice fields of Guyana’s economy. Yet, life often redirects our paths, and for him, the challenges along the way only expanded his capabilities and strengthened his determination for greater goals.

His professional journey began in 2000 with an internship at the Guyana Sugar Corporation’s Blairmont Estate, lasting four months. Here, he managed crop rotations and soil health while leading teams of seasonal workers—men and women whose livelihoods depended on timely harvests. Under the Caribbean sun, he learned one of the earliest and most valuable lessons in leadership: it begins with listening. Walking the fields at dawn, conversing with cane cutters, mechanics, and other frontline workers revealed practical ways to boost efficiency. These experiences deepened his appreciation for ground-level perspectives—an outlook that would later enrich his work in public health.

Following this, he secured an advanced supervisory role in a CARICOM-funded rice project led by Cuban agronomists. This position demanded not only technical expertise but also cross-cultural communication skills. Mc Watt bridged the gap between Guyanese technicians and Cuban specialists, resolving language barriers and navigating import restrictions. He refined his negotiation abilities while balancing foreign stakeholder expectations with local realities such as erratic rainfall, aging irrigation systems, and volatile market prices. When the first experimental crop under his leadership succeeded, community leaders praised his collaborative approach—a recognition he humbly redirected toward the collective effort of the team.

A year later, Mc Watt was invited to teach at Belfield Secondary School, where he taught general science, integrated science, and technical drawing. The transition from agricultural fields to the classroom felt natural. He enjoyed the routine of writing lessons on the blackboard, explaining soil profiles, and teaching basic anatomy. Many of his students were children of sugar workers, eager to connect textbook knowledge to the world they saw every day. To make learning more practical, he introduced projects such as building aquaculture facilities for tilapia and establishing school vegetable gardens—reinforcing his belief that knowledge gains its true value when applied to benefit the community.

Teaching was not without its challenges. With up to thirty-five students per class and limited resources, creativity became a necessity. Without formal laboratories, he demonstrated cell division using coloured beads and had students without drafting tools sketch on cardboard. His inventive teaching methods paid off—his students consistently outperformed the regional average in annual exams, proving that determination and imagination can overcome limitations.

Still, something was missing. During clinical screenings for parasites in farming families, Mc Watt’s early passion for medicine resurfaced. Borrowing physiology and pathology books rekindled his ambition, and his mentors recognized his unique blend of leadership skills and compassion, advising him to combine both in his career.

This advice coincided with a collaborative initiative between Guyana’s Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Health on veterinary-public health relations. Selected for the Diploma in Animal Health and Veterinary Public Health at the Agricultural School of Rupununi, he immersed himself in studying zoonoses, evacuation procedures, and sanitation inspections. He came to understand that in rural areas, where humans and animals often share a single water source, the health of livestock is a direct indicator of the community’s health.

Upon completing his studies, Mc Watt joined the Ministry of Health as a Veterinary Public Health Inspector. For more than a year, he conducted slaughterhouse inspections, supervised rabies control programs, and led community workshops on safe meat handling. When a rabies outbreak threatened both cattle and residents, he organized and managed an emergency vaccination campaign—distributing vaccines, training local volunteers, and restoring public confidence in the region’s health system.

PHASE 3: Reclaiming the Dream "Becoming a Doctor in Cuba"

“Education is the passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs to those who prepare for it today.” — Malcolm X

Amid his ten years of experience in agriculture, teaching, and veterinary public health, Cerdel Mc Watt longed to pursue his childhood passion of becoming a medical doctor. With an adoring heart that resonated since childhood, in 2005, he accepted a government scholarship and relocated from Guyana’s coastal plains to the verdant tobacco fields of Pinar del Río, Cuba. There, he enrolled in the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM). Nothing could fully prepare him for the whirlwind of immersion into a foreign culture and dialect, and the academics that awaited him, despite the respect that came his way for his post-graduate degree in agriculture and public-health.

A New World in Spanish

Cerdel’s surreal experience started on the first day at Sandino, a new small town named after the Nicaraguan revolutionary—now there was no escape, Spanish was the new compulsory language! He enjoyed the melodious Castilian that rolled off the locals; Spanish was the lingua franca for every room and corridor. The patients also added to the allure—for the first time he encountered people who had learned to appreciate casual conversation like “what brings you to your current ailment?” Oh, the praise was more than welcoming!

Cerdel had under a new prestigious goal and the style required was mastering vocabulary with the added challenge of receiving instruction in another language. In his head it had to “go” or perish. Six roommates later and his time was consumed, not that it was wasted, as his fellow student sampled from Ontario, Haiti, Zambia and rural Mexico and voilà, they blended into a singular idea.

Rigorous Curriculum, Cultivated Resilience

ELAM’s curriculum blended theory and practice from day one. Mornings began at dawn with basic sciences—biochemistry in crimson-stained amphitheatres, anatomy in air-conditioned labs where human torsos rested in glass cases. During the afternoons, the focus transitioned to community clinics: supervised by faculty, students diagnosed common ailments in neighbourhood consultorios. This fostered the understanding of bedside manner as well as resourceful diagnostics when supplies ran low.

Cerdel’s childhood recollections consist of tracing pulse points by lantern light during power outages, and soothing elderly patients with the gentle words, “Are you sure you’re trained enough?” His response was, and always would be, “Yes” said with a gentle nod and an earnest smile.

Cultural Immersion and Camaraderie

As is evident, cultural exchange wasn’t limited purely to the classroom. It was outside the classroom where it flourished. Cerdel and his classmates, on Saturday afternoons, would come together to partake in Guyanese curry and Ropa Vieja, and enjoy calypso-son blends through a Domino tournament unlike any other beneath the enormous ceiba trees. He discovered that laughter, like medicine, crosses linguistic barriers.

When he returned home on occasional breaks, his Spanish-inflected accent and tales of Cuban solidarity surprised friends and family in Georgetown. But they also ignited pride: their “Ithaca boy” was now part of an international community of healers.

Trials and Triumphs

Not all days were bright. The isolation of being thousands of miles from home tested his resolve. He wrote letters to his mother on onion-skin paper, chronicling minor scrapes of homesickness: missing Guyanese cassava bread, the polished ferry ride across the Corentyne, the comforting rhythm of patois. At times, academic setbacks—a failed pharmacology quiz or a correction in suturing technique—stung deeply.

Yet each failure became a learning moment, echoing a lesson he would later share with public health teams: “Identify the error, adjust the approach, and persist.”

From Pinar del Río to “Gueron” and Beyond

After four intensive years in Sandino, Cerdel transitioned to the Faculty of Gueron in Lajwana, rotating through the Al Barang teaching hospital for clinical clerkships. Here, he encountered advanced specialties—internal medicine, obstetrics, paediatrics—and refined his diagnostic acumen under mentors who demanded both precision and empathy. Night calls in the paediatric ward, managing neonatal emergencies with minimal staff, reinforced his belief that the human spirit can persist amid scarcity.

Intern Year and Return Home

In 2011, having passed rigorous exams and clinical competencies, Cerdel completed his intern year back in Guyana—rotating through Georgetown Public Hospital, Suddie Regional, and New Amsterdam Regional. He applied techniques learned in Cuba—preventive screening, community health education, and holistic patient engagement—transforming wards with fresh protocols.

When he donned his Guyanese medical license in early 2012, he carried two passports of knowledge: one stamped with Cuban resilience and another steeped in his homeland’s cultural richness. By journey’s end, the boy who once kneeled beside a silent cot in Ithaca had become a physician equipped to diagnose not only ailments but socio-cultural determinants of health. The dream, temporarily deferred, had come full circle—fortified by international solidarity, linguistic mastery, and a deeper conviction that healing transcends borders.