“Wherever the art of Medicine is loved, there is also a love of Humanity.”

Introduction

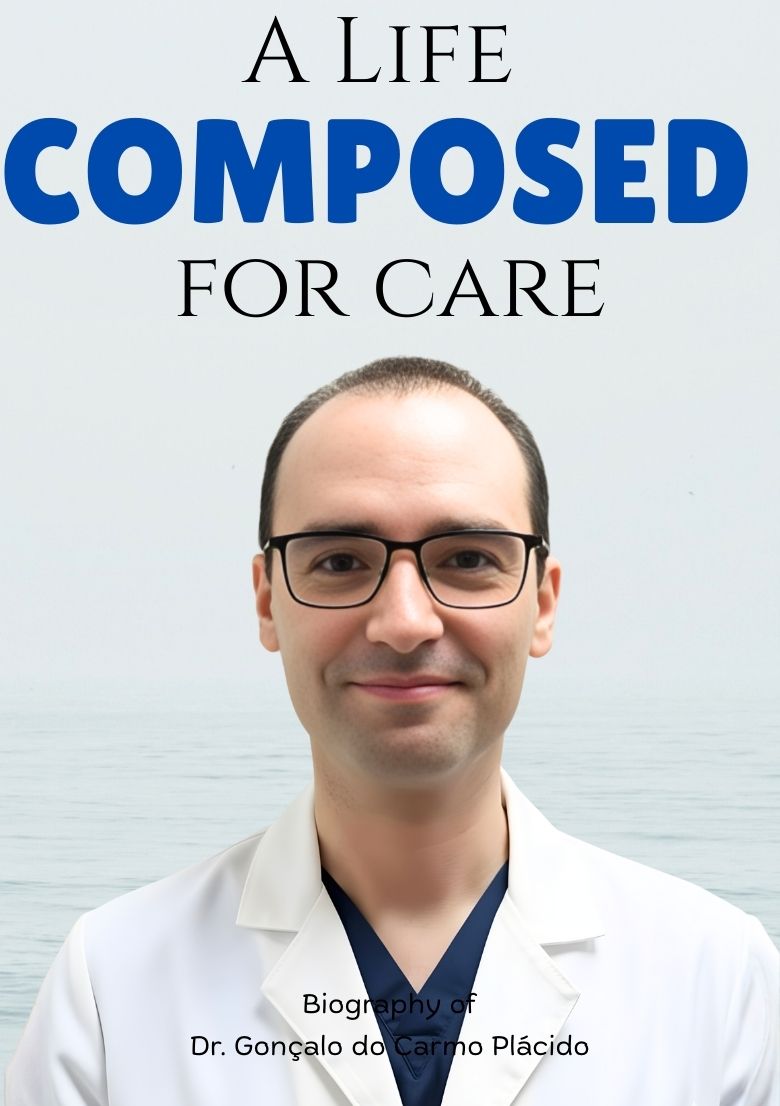

There is a grammar for every job. In healthcare, it is the grammar of attention, handoff, escalation, and de-escalation. Dr. Gonçalo learned this grammar early on and has been working on it ever since. He thinks that even the smallest habits can add up to safety and that the first conversation at shift change sets the tone for the whole unit. His life shows how routine can make someone reliable and how one nurse can change the mood of a whole service.

He was born in the late spring of 1988, the second son in a family that valued learning and helping others. He grew up in Lisbon, where music and language classes were a way of life. When he was six, English came into his life, not as a subject but as a way to get to know more people. He was playing the piano by the time he was nine, and for the next ten years, scales and études were as useful to him as textbooks. Music taught him how to keep time, listen, and be calm when performing in front of others. These skills would later help him stay calm in a clinical setting.

He volunteered as a responder for the local fire department when he was 17. He learned the ethics of arrival: greeting, assessing, stabilising, and communicating. He also learned the Portuguese Sign Language that season. He spent a month doing it and came away with a lasting respect for communication that doesn’t use words. These events confirmed an instinct that had been there since he was a child: he belonged with people at important times. Nursing was the closest way to reach that calling.

His training years were challenging and fun. His clinical rotations required him to be careful and patient. He discovered that expertise is an interdisciplinary dialogue and that the most effective enquiries are frequently straightforward questions posed at the appropriate moment. He also learned that being sympathetic doesn’t mean being sentimental. It is the disciplined effort to see what the patient sees, know what the family knows, and then act clearly.

What sets his path apart is how he kept taking on more and more responsibility. He went from bedside to team, then from team to unit, and finally from unit to organisation. Each expansion had classes and credentials, but the most important part was the habits that came with them: brief, effective huddles; incident reviews that looked forward instead of blaming people; and indicators that meant something to the nurse at the bedside. People called him when they needed to turn a repeat into a lesson and a lesson into a new normal.

This introduction sets the stage for the chapters that follow. The first part tells the story of the early years and how the character was formed. The second one looks at how to become a nurse. The third part comes after the Portuguese chapters that made up his clinical backbone. The fourth talks about the move to Riyadh and the duties that came with it. The fifth looks at how things have changed from projects to culture. The last part looks at research, teaching, and the long-term goal of a career spent making places where safety, dignity, and excellence are normal.

“The child is father of the man.”

Phase 1: Early Years and First Callings

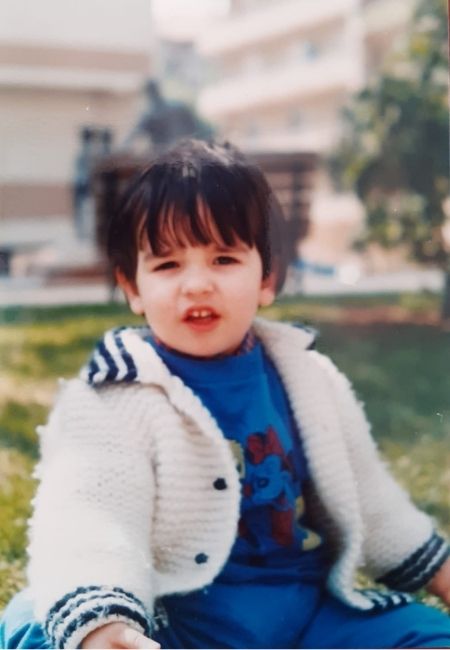

The quiet, steady presence of his family is what Dr. Gonçalo remembers most from his early years. He was born on May 1, 1988, in Lisbon, Portugal. He was the second son of João Bernardes Plácido and Zulmira Maria Zeferino do Carmo Plácido. His childhood was spent in a house where education was expected, discipline was modelled every day, and compassion was the unspoken language of care. His father taught him the importance of honesty and hard work, and his mother made sure that he and his older brother knew how important it was to respect other people. His brother was both a rival and a friend. Just being around him made him want to push his limits, and seeing his brother’s success made him want to do even better.

The family home in Lisbon was more than just walls and rooms; it was a place that shaped who they were. People shared meals at a table, where they told stories, learned things, and laughed. His mother’s voice often reminded them that respect was not up for discussion, and his father’s example showed them that doing honest work had lasting value. They created a space where both sons learned that being kind and strong is something you should do every day, not just when things are tough.

Dr. Gonçalo distinguished himself in school from the start, not only for his intelligence but also for his ability to interact well with others. Teachers often said that he was polite, reliable, and paid attention. His classmates asked him for help with their homework because he was patient and didn’t talk down to them. He was just as happy to share notes with a classmate who was having trouble as he was to have a lively debate with his teachers. He didn’t want to be recognised; he wanted to be understood. He liked to listen first and then talk. This natural ability to listen would later become one of the most important skills in his clinical career. Dr. Gonçalo started learning English when he was six years old. His ability to learn English, which most Portuguese kids his age could not match, demonstrated the intelligence of both his parents and his desire to explore the world.

“I attribute my success to this: I never gave or took any excuse.”

Phase 2: The Making of a Nurse

Dr. Gonçalo’s character would be tested and improved when he started at the Nursing School in Lisbon. The transition from adolescence to higher education was not merely an age-related change; it was a purposeful entry into a profession that required a balance of intellect, resilience, and compassion. The institution itself was a shining example of strictness, where theory and practice were always linked and every lesson had real-world consequences for patients. For Gonçalo, the Nursing School was more than just a place to learn; it was a place where he could change.

The first classes taught him a lot about anatomy and physiology. Diagrams of the human body, textbooks full of jargon, and endless practicals all required discipline. But he didn’t just see organs behind the lines of vessels, nerves, and muscles; he saw people whose lives would one day depend on what he knew. The responsibility that came with each fact he learned and every procedure he practised really hit him early on. It wasn’t about getting good grades; it was about making people trust him so that they could rely on him later. This feeling of duty kept him up late studying and gave meaning to the long hours he spent reviewing case studies and literature available.

But the classroom was just the start. During his clinical rotations, he learned about the reality of being a nurse. It was an unforgettable experience for him as a student nurse to enter a ward for the first time. The smell of antiseptic, the sound of footsteps in the hallways, and the beeping of monitors were all new to him. These weren’t rehearsals; they were real lives, and he was supposed to help. With the guidance of his supervisors, he learned how to clearly introduce himself to patients, maintain eye contact, and build trust even before he touched their hands. He quickly realised that technical skills were only one part of the equation; being present and able to communicate were just as important.

“The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.”

Phase 3: The Portuguese Chapters

Dr. Gonçalo began a new chapter in his life when he transitioned from being a student to a professional. This chapter is all about serving his home country. The years he spent in Portugal were the building blocks for the international work he would do later. There were years of testing, full of the realities of bedside practice, and the first experiences of being a leader. He found ways to improve not only his technical skills but also his moral and emotional compass in every ward, clinic, and operating room.

His first steps into Portugal’s healthcare system were in community care, where health was measured not just by tests but also by the stories of families and the rhythms of everyday life. He entered the patients’ personal worlds with the professional knowledge of a nurse and the humility of a guest. He heard older patients talk about how lonely they felt as they got older, and he saw parents worry about their kids with chronic illnesses. These early experiences made him believe that nursing was as much about the situation as it was about the care.

In the operating room and post-anaesthesia care unit, he learned a different pace: the need for accuracy, the discipline of sterile technique, and the choreography of a team where every move counted. Dr. Gonçalo learned how to stay calm in the noise of machines and the fast conversations between anesthesiologists and surgeons. After surgery, patients were on a fragile line between complications and recovery, so post-anaesthesia care required a lot of attention. He honed his observational skills, discovering that, in a minute, there could be a modification in breathing patterns, a nuanced alteration in consciousness that frequently indicated more significant realities. The severity of these changes instilled in him a deep respect for being ready. Being unprepared meant risking a life; being prepared meant saving one.

Cardiology put him in another tough field. Portugal’s public hospitals were very busy, and the cardiology wards were full of complicated cases. Heart failure, arrhythmias, and acute coronary syndromes are all conditions that need quick treatment, but also long-term advice on how to live a healthy life. He learned how to balance the need for quick care with patient follow-up education. He learned how to convey adverse news to patients in a kind way, telling them to change their diets or comply with their treatment plans without judging them. He understood that the heart was both a body part and a symbol. It took more than medicine to heal it; it took trust, honesty, and a carer who would always be there, even when things were uncertain.

Infectious diseases tested another part of his personality: how brave he was when things were dangerous. Being around pathogens in the air and on surfaces required constant watchfulness. He learned how to keep himself safe without making his patients feel like he was too careful. It became second nature to follow infection control rules. He also saw the stigma that often came with these diseases, which was more than just the technical side. Patients had concerns with microbes, loneliness, fear, and sometimes shame. Dr. Gonçalo took it upon himself to bring back dignity. He talked to them like he would talk to any other patient, making sure they were considered whole people and not just their illness.

Note of Thanks

When we write a biography, we realise that no one’s life is ever truly alone. This biography narrates the story of Dr. Gonçalo do Carmo Plácido, but many other people have helped, shaped, and inspired him along the way. It would be wrong to end the story without thanking all of these people, voices, and hearts. This note of thanks is not just a formality; it is a real acknowledgement of the people and events that made this biography possible and, more importantly, gave the life it tells meaning.

First and foremost, his family should be thanked. His parents, João Bernardes Plácido and Zulmira Maria Zeferino do Carmo Plácido, gave him the base on which everything else has been built. Their guidance, sacrifices, and unwavering presence instilled in him the values of honesty, humility, and dedication. His brother, with whom he had a rivalry, shared jokes and grew up together, giving him both challenges and support that made him stronger. The family home was a safe place where discipline and love were always present. It was a place where caring for others was not just a conversation, but a daily practice. Without this soil, his roots wouldn’t have grown deep, and his branches wouldn’t have been able to reach far. His wife, the backbone of his success.

He is thankful to the teachers he had as a child and teenager for helping him grow as a person and as a thinker. People who taught him English when he was young opened up a world of knowledge and cooperation. People who helped him love music taught him how to be disciplined, creative, and able to say what he couldn’t say. People who taught him Portuguese Sign Language made him more empathetic and showed him that human connection goes beyond sound and speech. Their lessons went far beyond the classroom, following him into hospital wards, research committees, and meetings of leaders.

This note of thanks should include the Algueirão Mem-Martins Fire Department. He first learned what it meant to serve in times of need, with other volunteers and professionals, and with the sound of emergency sirens in the background. Those coworkers and mentors who welcomed a young man of seventeen and trusted him to meet the demands of the job gave him faith that he could stay calm in a crisis. The lessons he learned from those early calls helped him stay calm in the clinical setting later.

He is just as thankful for the professors at the Nursing School of Lisbon and the Portuguese Catholic University of Lisbon. They wanted strictness, responsibility, and humility. They corrected mistakes, sometimes harshly, but always with the goal of making a nurse who was both skilled and caring. His classmates, who became friends, study partners, and companions on long days of study, also deserve appreciation. Together, they built strength, made connections, and celebrated important events that would impact their careers later on.

The Portuguese parts of his career brought people into his life who had a lasting impact on him, including mentors, coworkers, and patients. In community care, elderly patients who welcomed him into their own personal worlds taught him that health is always affected by the situation. In operating rooms and post-anaesthesia care units, colleagues who worked well together showed how to trust each other. In cardiology, infectious diseases, oncology, and chronic pain, he met both patients and professionals who reminded him every day that courage is not the lack of fear but the choice to act anyway. He is very grateful to every patient who let him into their story and trusted him when they were weak. They were not just people who needed care; they were also teachers of strength, patience, and respect.

Thanks

Dr. Gonçalo do Carmo Plácido