“Your beginnings do not define your ceiling. They define your foundation.”

Introduction

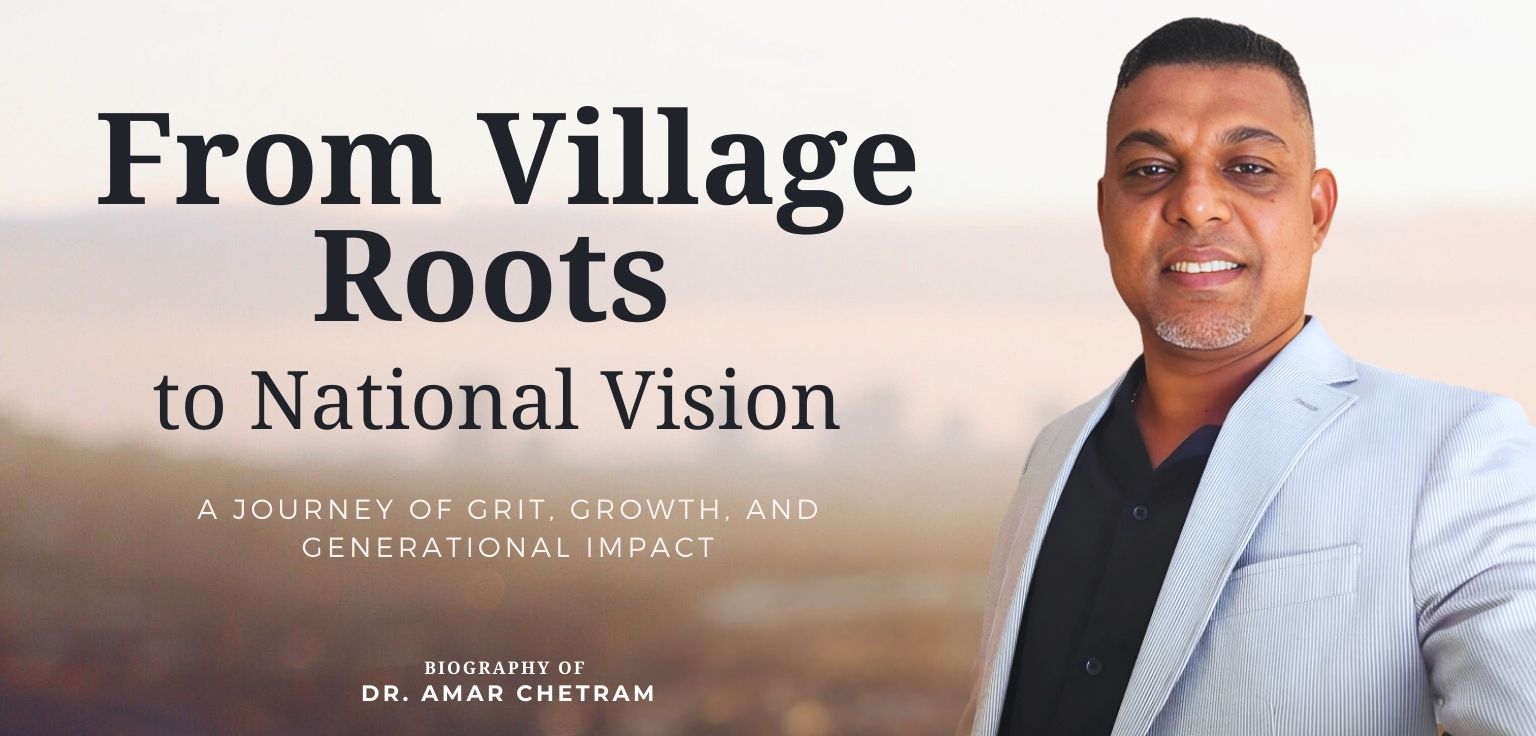

The story of Dr. Amar Chetram is not just one of entrepreneurship or achievement. It is the story of a man who has lived multiple lifetimes in one—a boy raised in poverty who became a builder of industries; a schoolchild who missed most classes but graduated among the top in his school; a government employee who left security for uncertainty; and a visionary who now employs thousands, dreaming not just of more companies, but of becoming a major servant to his country.

He was born on March 3, 1982, in the heart of Georgetown Public Hospital, Guyana’s capital city, but his roots run deeper into the rural village of Blake on the East Bank of Essequibo. He grew up in Hubu, a village of barely 200 people—defined more by its resilience than its resources. It was here, between cassava fields and muddy lanes, that Amar first learned what it meant to stretch a dollar, share a meal, and dream beyond your reality.

In a home where his father labored on farms and his mother managed the household, Amar learned two things early: hard work was non-negotiable, and education was a privilege—not a given. He walked and travelled miles to reach Leanora Secondary School, often missing classes due to financial constraints, yet managing to pass each year with quiet determination. Out of 350 expected school days, he sometimes only attended 60—but his will to learn was never absent. When it came time to write his exams, he passed five of six subjects, emerging as the most improved graduating student.

These formative years shaped not just his intellect but his instinct. He understood logistics before studying it formally. He navigated risk long before entering the business world. And perhaps most importantly, he knew early on that if he wanted a better life, he’d have to build it himself.

He began humbly—working at Banks DIH, then at the Guyana Revenue Authority as a customs officer, where he learned the intricacies of trade, import regulations, and supply chains. But it wasn’t enough. Stability was never the goal—impact was. So he resigned and chose the harder path: entrepreneurship.

From selling knockoff brand clothes sourced through Yahoo Messenger, to losing his entire investment in a container scam in Pakistan, to launching a sawmill business when he couldn’t sell the machines—every chapter of his life has been built on the ruins of the previous one. Each loss became a stepping stone, each failure a platform.

What followed was a string of enterprises that not only rebuilt his life but reshaped Guyana’s industrial landscape: roofing factories, sawmills, construction companies, and most notably one of Guyana’s largest oxygen production facility—a critical player during the COVID-19 crisis. His group, the CB Group of Companies, now spans five sectors and employs over 250 people directly—not to mention thousands more indirectly through subcontracting, suppliers, and regional expansion.

Phase 1 : Humble Beginnings in Hubu

“You don’t choose where you’re born, but you can choose what you build from it.”

In the quiet countryside of Guyana’s Essequibo region, nestled between narrow dirt paths and banana trees, lies a tiny village known as Blake. It was here, on March 3rd, 1982, at Georgetown Public Hospital, that Amar Chetram was born into a world that offered few luxuries but infinite lessons. Though his birth took place in the capital city, it was in the neighboring village of Hubu—just three kilometers away—where his life would truly begin, shaped by the soil, the sweat, and the sacrifice of a rural upbringing.

Hubu, a village of about 200 residents, wasn’t marked by its infrastructure or modern conveniences. What defined it instead was its community resilience—a place where neighbors became family, and survival was a shared effort. Life moved at the pace of the river, and work was done with bare hands sun-scorched skin, and relentless will. There were no grand estates or golden opportunities—only the quiet hope that tomorrow would be just a little better than today.

Amar’s father, a laborer, worked tirelessly in the agricultural trenches of Guyana. He toiled in cassava fields, harvested plantains, and took on odd jobs—cleaning drains, selling fruits, and doing whatever was necessary to provide. He was not a man of titles, but he was a man of principle and grit, and that left a deeper mark than any certificate ever could. His hands may have been calloused, but his heart was soft, and in every sacrifice, he made, Amar absorbed the quiet lesson that work was sacred.

His mother, a dedicated housewife, held the family together with little more than love and sheer resolve. Her days were spent cooking over open fires, keeping a modest home in order, and praying that her children might one day escape the cycle of poverty.

Together, his parents formed a pair of unsung heroes—people who had little in their pockets but abundance in values. They raised three children, including Amar, in a home where education was a dream they couldn’t always afford but never stopped believing in. While other families spoke of careers, Amar’s family spoke of survival. Yet, even without abundance, they gave him the most priceless gift of all: belief in his worth.

Education began at Blake Nursery School, a modest building where Amar first learned his ABCs—often with more distraction than direction. From there, he continued to primary school, both situated in the same compound due to the small village population. Resources were scarce. Students shared benches. Textbook were reused. Chalk was precious. And yet, those early classrooms—though humble—became the cradle of his ambition.

Phase 2 : Trials of Education and Determination

“I didn’t miss school because I was lazy. I missed school because life made me choose between learning in a classroom and surviving outside it.”

Education is often hailed as the great equalizer, but for Dr. Amar Chetram, even access to education was a battle he had to fight—not once, but constantly.

After securing 424 marks out of 486 in the Common Entrance Examination, Amar was placed at Leanora Secondary School, a Grade C school that, while not elite by national standards, stood as a symbol of possibility in his life. The placement alone was a feat, especially coming from a village where most children didn’t make it past primary school.

But dreams don’t ride the bus for free.

Leonora Secondary was nearly 30 kilometers away from Hubu. To get there, Amar had to wake before sunrise and catch two different minibuses vehicles jammed with more students than seats, and often driven without schedule or safety. On many mornings, the fare wasn’t available. Some days, there was barely food at home. School had to take a backseat toworking on the farm, planting vegetables, or helping with odd jobs just to make ends meet.

In a typical academic year of over 300 school days, Amar was lucky to attend about 60. And yet, he kept going—not just physically, but mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. He studied when he could, listened more than he spoke, and clung to every bit of knowledge like it was a lifeline.

While some of his peers had private tutors and stable schedules, Amar became his own teacher. He learned how to focus in short bursts, how to retain information on the go, and how to prioritize survival without letting go of the dream. His resilience was his education.

It was not about perfect grades. It was about passing—surviving one more term, one more exam, one more step forward.

By the end of his five years at Leanora, he sat for the CXC Examinations, equivalent to the GCE O-Levels or SATs. With minimal classroom exposure, limited resources, and no formal academic support, Amar passed five out of six subjects—falling short only in mathematics. But his achievement wasn’t measured in marks. It was measured in determination. He was awarded the title of “Most Improved Graduating Student”—a quiet recognition of a loud struggle that most never saw.

And even in that moment, he wasn’t satisfied.

Phase 3 : From Laborer to Leader – The Early Professional Climb

“I didn’t wait for a perfect opportunity. I took whatever job I could, then gave it so much value that the job had to rise with me.”

For many, the transition from school to work begins with polished résumés, job fairs, and interviews with opportunity knocking. But for Dr. Amar Chetram, that door didn’t just fail to knock—it was never built for people like him. So he made one himself.

Fresh out of secondary school, carrying five CXC subjects and the title of Most Improved Student, Amar began his professional journey the way many do: at the bottom. But he wasn’t looking for prestige. He was looking for a starting point.

That point came at Banks DIH, Guyana’s largest beverage and brewery company. It was a place many aspired to work at, known for its structured systems and reputation. He walked in, applying for a position as a warehouse clerk—but was instead hired as a laborer. There were no fancy desks or air-conditioned offices. The job meant lifting crates, stacking boxes, and getting his hands dirty—day in and day out.

Most people would have seen it as a setback. Amar saw it as training.

Within six months, his diligence, discipline, and refusal to cut corners earned him the very position he initially applied for—warehouse clerk. And within a few short years, he rose to the rank of supervisor.

Every day on the warehouse floor was more than a shift—it was a classroom. He learned inventory systems, supply chains, dispatch logistics, and the subtle art of leading people who had been in the job far longer than he had. He developed a work ethic rooted in respect, not hierarchy. Whether it was loading stock or preparing reports, Amar did it with quiet precision and unmistakable hunger.

The warehouse was located in Georgetown, while Amar still lived in Hubu. That meant a daily round trip of over 100 kilometers, two buses each way, and hours spent in transit. Often, half his salary went to transportation. What remained barely covered household expenses. After five years of loyal service and professional growth, he stood at a crossroads.

He asked himself a question that would change everything, So, with no savings, no safety net, and nothing more than raw courage and curiosity, Amar made a bold move. He resigned from Banks DIH—leaving behind stability in pursuit of something uncertain: entrepreneurship.